Deadly words, part 2--CUES & CUEING

They kill communication, maybe even thought.

CUES and CUEING. I devoted a previous post to three-cueing, so I’ll try to avoid too much repetition.

“Cues,” or one of its inflections, “cueing,” becomes a DEADLY WORD when preceded by “three-.” (Same with another inflection, “miscue.” That’s to come.)

Three-cueing is part of the “balanced literacy” world view I discussed in the preceding post. As you no doubt recall, “balanced literacy” generally refers to “programs with ‘a bit of everything’ [or maybe a lot of everything] and typically involving limited and nonsystematic phonics instruction [🎯].”

“Three-cueing” and “balanced literacy” might actually be different words for the same thing: An approach to teaching reading where learners who come to a word in text they don’t recognize are taught to use a variety of “cues” rather than to prioritize letter-sound knowledge. Letter-sounds, according to this perspective, is only one of several possible cues and probably not even the most important. Instead, the word’s context—the text and the words that come before and after and illustrations on the page—provide cues that are at least as, and possibly even more, important than letters and sounds.

I wonder sometimes if a typo slipped in at some point, because it seems to me that what the balanced literacy/three-cueing people are talking about is actually “clues,” with an l. Students are asked and prompted to ask themselves questions in order to read a word they don’t recognize by sight. Sometimes it’s called “solving” a word, making it seem like detectives working to solve a mystery: What would make sense here? What’s the first letter? What’s in the picture(s)? What’s the last letter?

One source of ambiguity in this arena is what exactly are the three cues that three-cueing advocates and practitioners are talking about? One version comprises semantic (meaning), syntactic (words’ arrangement in a sentence), and orthographic (the spelling system) cues. Another version, associated with Lucy Calkins and called MSV (or M/S/V: meaning, syntax, visual), uses the same first two cues (meaning and syntax), but invokes visual cues instead of orthographic cues.

If a student makes an unsuccessful attempt at reading a word, a question that would be used to cue visual cues might be, Does it look right?

What’s puzzling about this is if a novice reader hasn’t yet firmly associated written spellings with words and hasn’t seen the word spelled often enough to have a sense of what it should look like, prompting (or cueing) “Does it look right?” seems unlikely to help read, recognize, or solve a word.

Calkins distanced herself from three-cueing by saying, “I do not know anyone [herself presumably included] who defines his or her method for teaching reading as ‘the three cueing system.’” Maybe it’s a coincidence, but her version of “balanced literacy”—a term from which she famously does not distance herself—contains exactly three cues, which she doesn’t call cues nor give an exact number. She designates MSV (or M/S/V) as “multiple sources of information.” If this sounds to you like “three-cueing” with a different label, you’re not alone.

Three-cueing or MSV or multiple sources of information—whatever it’s called—is actually not a bad way to describe what mature readers do, as David Pearson pointed out almost 50 years ago. Once you know how to read well enough, you will use multiple cues, whether there are three of them or some other number or you call it something else.

“The brain is a predictive machine,” the neuroscientist Stanislaus Dehaene points out. Whether listening or reading, it looks behind to anticipate what’s ahead. Ultimately, it’s a word’s letters that determine how the word is read, but the meaning can depend on the context: Does the word “bat” in a text signify something to swing or something to avoid getting tangled in your hair?

Or consider “through” and “threw.” They are pronounced identically, have different meanings, and have orthographic features that are more regular (th, r) and less regular (ought, ew). Sorting through all that (I just threw that in) when coming across one of these words in a text, and recognizing what the correct word is, requires a fairly well-honed cognitive-linguistic apparatus.

Then getting to this point requires the brain’s reading machinery (or circuitry) to work smoothly and in sync. That machinery/circuitry does not yet exist in beginning and early readers, so orchestrating multiple cues is not actually possible until a certain level of reading proficiency is attained.

As with “balanced,” “cue” is a useful word that has been appropriated (hijacked?) to describe a fundamentally unsound way of teaching reading. But, also as with “balanced,” we can—if we want to—salvage “cues” in teaching reading. All it takes is realizing that not all cues are created equal and of equal value when teaching students, or anyone, to read.

Letter-sound cues, more precisely, “grapho-phonic” cues, are the most important because they are the most reliable way to read and recognize a word that is not recognized at sight. This is true even in a complex and not totally regular orthography as English uses,1 which, not incidentally, is more regular than irregular.

But even grapho-phonic cues, usually called “phonics and decoding,” are not perfect for recognizing words accurately (remember: bat), and are particularly not perfect in a complex orthography such as in English (through and threw).

Context cues provided by the surrounding text and illustrations can and often must kick in. But they play a secondary, or confirmatory (or dis-confirmatory), role to help recognize words accurately. Context cues are not co-equal to letter-sound cues.

The moral of the story, once again, is we need to be precise when using words that can be fatal to communication, understanding, and getting clarity on practices most likely to obtain desired results.

There is nothing inherently wrong with the word “cue,” nor should we try banishing it.

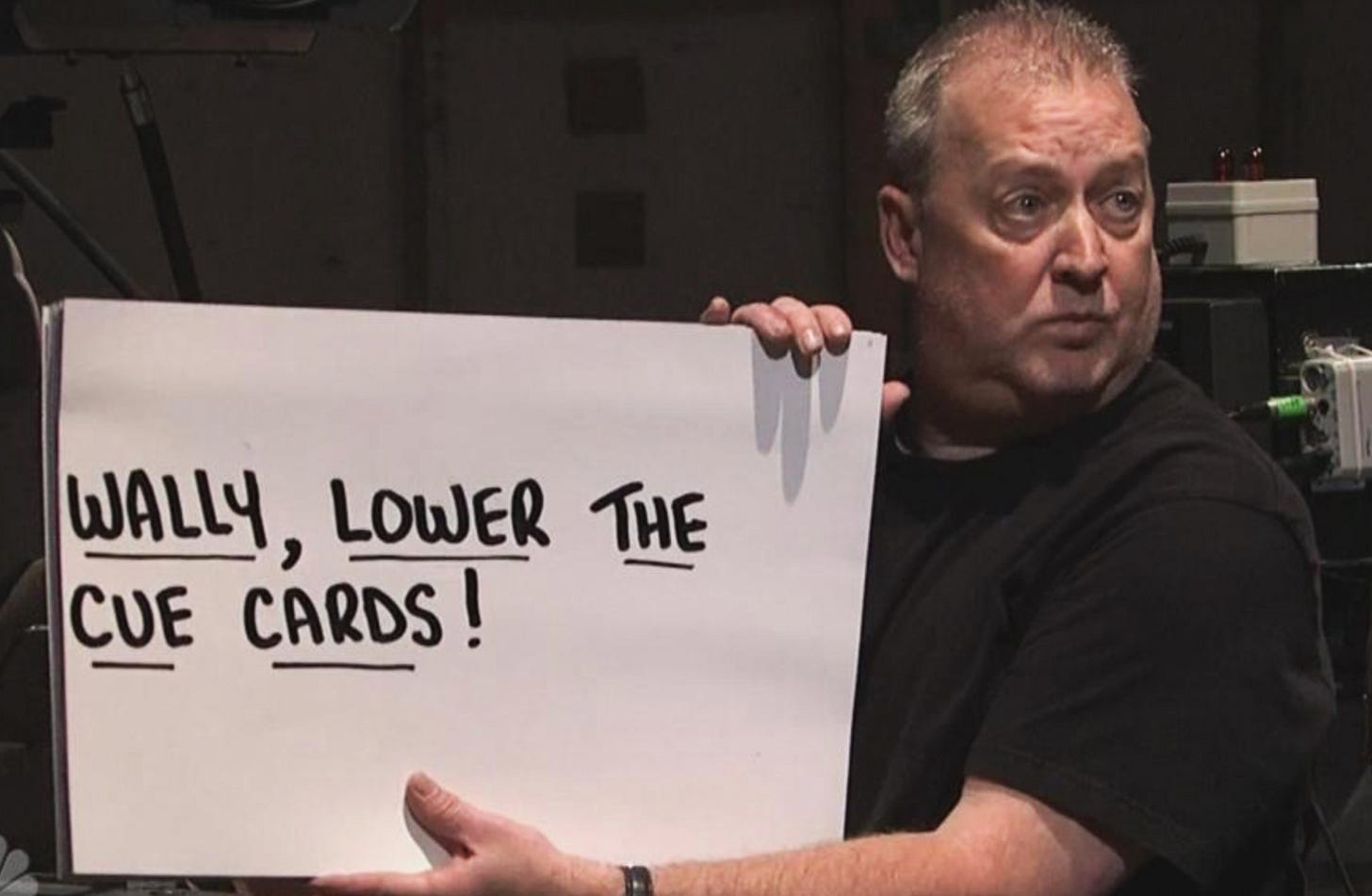

What would actors do if they didn’t know to listen for when to go on or to speak? Or if we didn’t pay attention to those signals from others telling us we’re talking too much or are offensive or, alternatively, are interesting and engaging? What would we do if at least some people didn’t know to pay attention to social …. cues?

Even in reading instruction, cues can be productive if we understood what they mean. Cues are actually a very well-established concept in education. It signifies providing students with “instruction as to what is to be learned as well as directions as to what the student is to do in the learning process.” Combined with student participation (i.e., engagement) and teacher feedback, well-crafted cues have been shown to produce robust effects on student learning in virtually all subjects.2

Recall what I previously reported that Tim Shanahan wrote in his blog: “In the 60 years since three-cueing was proposed, there is no direct evidence that teaching it improves reading.” The explanation for this, I am guessing, is that the definition of “cues” used by three-cueing is an aberration, a departure from a truer meaning of the word. Combined with the ambiguities and inconsistencies noted above, these create an incoherent stew that leaves students largely on their own to figure out how this thing called reading works. Some get it. Many, maybe most don’t. But no better and maybe no worse than whatever else passes for reading instruction.

But using the right sorts of cues, along with other well-known but inconsistently utilized teaching practices, teachers can demystify the reading process for students. To do so, they must show students how written language represents oral language by mapping speech to print. Then as this process unfolds, teachers must simultaneously, but not at the exact same time, develop students’ oral language, knowledge, and other skills and dispositions. The net result is more likely to be a robust “reading circuit” where progress in reading propels language development and knowledge growth, and language development and knowledge growth help advance reading development. Cues, properly understood, and other features of effective teaching practicers have a role to play.

So I wouldn’t advocate getting rid of cues or cueing.

The word simply has had very bad associations in the reading world, which in turn has had very unfortunate consequences for too many students. The best solution, once again, is to strive for clarity and understanding. Banishing words, even those with bad associations, is too easy. Clarity and understanding are harder but much more likely to yield good results.

Cueing was promoted in England until 2006, but no longer is. Two memories from when it was:

1. 30-odd years ago, I went to a presentation by a teacher trainer who advocated the ‘Does it look right?’ strategy in exactly those words. I couldn’t understand at first what this meant, as the word which the child was looking at on the page presumably WAS right – i.e. correctly spelled and meaningful in the context. It turned out that what was meant was that the child would start by guessing the word, then check the printed word to see if it looked right for that guess. What he should do if it did NOT look right was not explained, and in any case, as Claude has said, a struggling reader is unlikely to have a clear idea of what the word SHOULD look like. The speaker was also in favour of accepting misreadings if they made sense, however, so I wondered what the child was supposed to do if the guessed word made sense but did not look right.

2. In 2002, England’s official Department for Education produced materials called ‘Early Literacy Support’ for children who were struggling with reading. The materials included a video in which a child was trying to read the word ‘soft’. Her lip movements showed that she was trying to sound it out under her breath and would probably have got it that way, but the adult interrupted her and said ‘What would make sense?’ In fact the context was not helpful from that point of view, but the adult’s intervention was presented as good practice.

Jenny.

Okay, Doc...you've piqued my interest. I have thoughts and questions:

1. Balanced Literacy (as you said last time) really needs to be defined. I feel like Inigo Montoya...

2. "Clue" probably is better than "cue." But how many teachers/classrooms/schools were actually teaching 3-cueing as a reading process? I don't know of any, and I can say it wasn't in widespread use in the LAUSD from '94 till now, but it still gets the blame for disappointing test results. I wonder if there is any data on this.

3. Would it be possible in your opinion to privilege the V (grapho-phonic) while still asking students to attend to the M and S? I have found that kids don't attend to meaning when they have a steady diet of decodables (often times not much sense or meaning to be had). Especially for EB students...I want them thinking about their reading and self-monitoring.

As always, thank you for your insight.

Gina