Teaching reading has its complications, but...

We have a useful synthesis, and three key ideas can further help illuminate.

Teaching reading—especially if your goal is to get everyone reading—is more challenging than most people realize.

It would be helpful to have an accessible and generally understood distillation of what research on reading and teaching reading tells us. This won’t reveal everything needed to teach reading successfully to everyone. But it will give us something at least as important, maybe even fundamental: Understanding.

Reid Lyon’s 10 maxims

Actually, we have something like that: A set of 10 maxims grounded in research, developed by G. Reid Lyon, former chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch at the National Institutes of Health who directed the NICHD Reading Research Network. I’ve discussed these previously here; the maxims themselves are here and in footnote1 if you can’t bear to click away from this post.

I would urge every educator and anyone interested in reading education to become familiar with them. If you’re feeling hardy, you might even consider dipping your toe into the voluminous research.

These should not be seen as the final and definitive word on reading and reading education. As is true with any body of knowledge—call it the “science of” or something like “what we know from the research”—research on reading and reading education is dynamic and evolving. People are often too quick to claim “settled science.” That term should be used sparingly and with extreme caution, particularly in the social and behavioral sciences. Yet there are a number of things that can be claimed with confidence; Lyon’s maxims capture many, if not most.

The maxims seem to me a compelling synthesis of decades of research that identify important and essential truths about reading and reading education. How these will look in 10, 20, or more years is up for grabs. But that doesn’t mean they can be ignored. They can’t and shouldn’t be.

Three key ideas that go deeper

I’d like to suggest here three key ideas that I believe underlie those maxims and can bring us to a fuller understanding of what’s involved in helping all students become successful readers. If Reid’s maxims are the “whats,” I hope these three ideas address the “whys.”

None of these is original with me. I’m relying on the work of other researchers and educators who have helped provide breakthroughs in my understanding and, I’m certain, that of others.

I rely to a great extent on neuroscience and, less so, on anthropology and human evolution. I make no pretense of expertise in these realms. Still, misinterpretations or misapplications are solely my responsibility. I would be very happy for any reader to correct, even with a slight tweak, anything that needs correcting or tweaking. I’ve already benefited from correspondence clarifying a couple of subtle but not unimportant points. I’ll even provide a comment button, which I’ve neglected in previous posts but will try to remember from now on.

Enough throat-clearing. Becoming a successful reader requires these three:

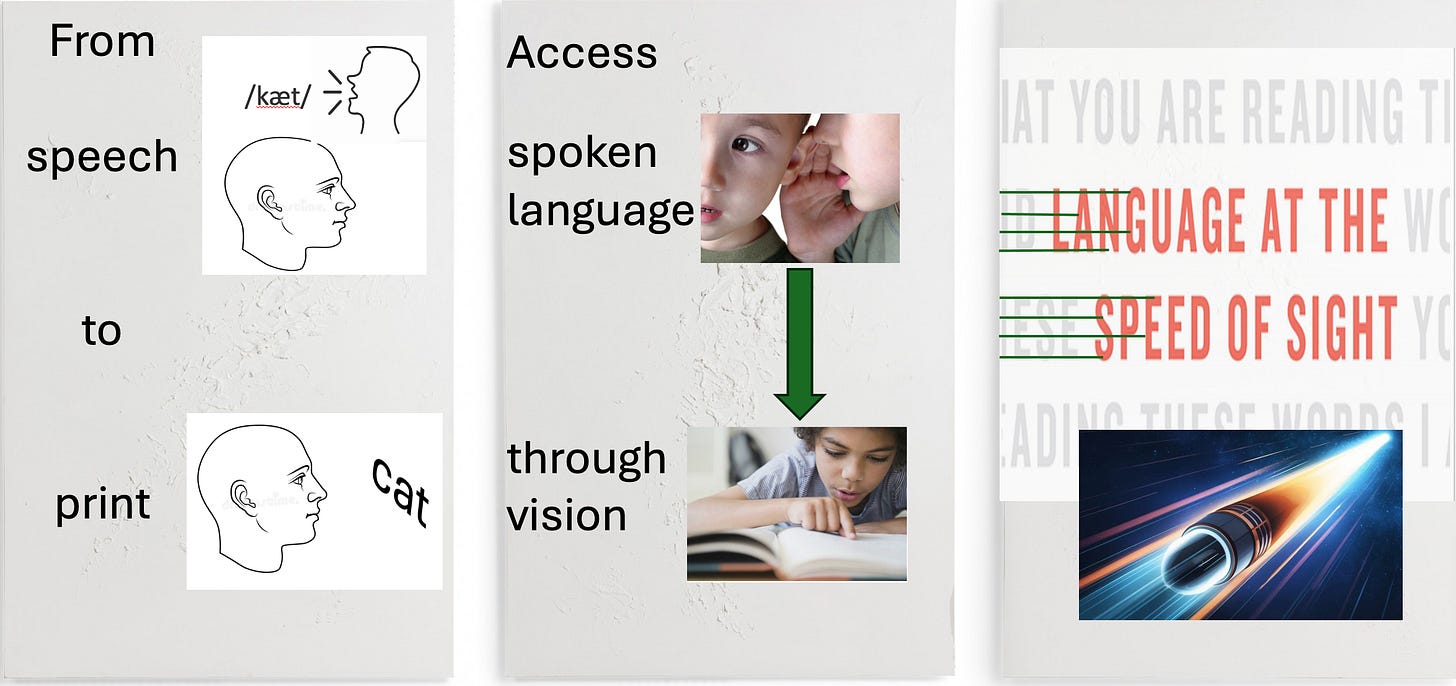

• going from speech to print;

• accessing spoken language through vision;

• language at the speed of sight.

A thread running through all three, although harder to spot in the third one, is connecting the language we hear and speak—known as speech—to the language we see and write—known as print. If this distinction seems strange or hard to fathom, please see two earlier posts: Oral language is for hearing. Written language is for reading. They're not the same thing, Parts 1 and 2.

These three apply regardless of the language you’re learning to read or if you’re learning to read in a language you already know or one you’re simultaneously learning as your second, third, fourth, etc.

1. From speech to print

The title of Louisa Moats’ classic text, Speech to Print, provides the punch line: Learning to read requires connecting the sounds of the spoken language to how those sounds are represented in print.

Connecting speech, which carries oral language, to print, which carries written language, is necessary, because spoken speech is part of our species’ evolution. Human speech appeared several hundred thousand years ago. We appear to be primed and ready to make sense of oral language—or at least pay attention to it for good evolutionary reasons—from birth2. Not so with written language.

Written language—print—was a much later human invention, about 5,000 years ago. Print is simply marks on a stone tablet, scroll, page, or screen until the connection is made between those marks and what they represent.

Just as oral language came before written language in human evolution, oral language also comes first in human development. Oral language acquisition is wired in at birth and generally acquired easily if we’re surrounded by people who speak and interact using oral language. Assuming no developmental anomalies, language acquisition is considered “natural.”

It’s not the same for learning how to understand and produce print, which, for languages such as English, is a visual representation of speech sounds.3 Learning to understand and produce print, that is, becoming literate, doesn’t typically happen as easily or by itself solely from being around people who read and write.

Such a context certainly facilitates literacy acquisition, but it’s necessary to provide at least some teaching of the system whereby speech is represented in print. Teaching and learning are also “natural,” but learning to read and write is harder than learning a language to which we are exposed early in life and for a number of years. Learning to read and write requires more focus and effort. For some individuals, very little focused effort is necessary; for others a great deal; most of us are somewhere in between.

If you’re going to be able to read well and fluently, making the “speech to print” connection is generally a must.4

2. Accessing spoken language through vision

(I covered some of this terrain in “Tierney & Pearson reply (III): On 3-cueing.”)

The neuroscientist Stanislaus Dehaene goes deeper into helping us understand why connecting speech to print is so important for becoming literate:

A vast brain circuit is transformed when we learn to read. … As a result, we gain the ability to access the spoken language system through vision. (from “Inside the Letterbox: How Literacy Transforms the Human Brain,” emphasis added)The seemingly simple phrase, “we gain the ability to access the spoken language system through vision,” belies the depth and breadth of its significance. Reading requires language we previously had only been able to access by hearing, that is, through the auditory perceptual system, to become accessible through a different perceptual system—visual.

This goes a giant step beyond “speech to print.” What Dehaene refers to is not simply connecting a language’s sounds (phonology) to written symbols (letters, or graphs). He’s referring to accessing the oral language system, all of it, which includes the vocabulary, syntax, morphology, discourse features, and the knowledge carried by or inhering in the language system. In short all the many ways that language creates and communicates meaning.

But the linchpin is the connection between the sounds of the spoken language—the speech—to how those sounds are codified into print. Simply put, speech to print.

Reading requires all of that, the sounds of and the meanings carried by oral language, be made accessible by sight. Why? Because when we see language in written form—print—the signal goes to a different part of the brain than when we hear language in its oral form—speech. When we read, what we had previously only been able to perceive, or access, auditorily now needs to be perceived, accessed, visually. For that to happen, the visual information provided by print must be connected to the oral language system. Such a connection in the brain does not exist at birth.

Two huge implications:

First, a “reading circuit” in the brain that connects the languages’ sounds, visual representations, and the spoken language must be created through some type of instruction. Think of it as “demystification.” It is not intuitive that print carries meaning, much less how to access it. As with “speech to print,” sometimes only a little teaching, or demystification, is needed; sometimes a lot; but at least some in virtually all cases.

Second, more robust oral language will contribute to more robust literacy skills and development. Comprehensive oral language development is also a must—just as “speech to print” skills are. If literacy and language are to develop to the utmost, there must be a focus on all aspects of oral language development, including knowledge and metalinguistic skills, before and during literacy acquisition, and oral language development must continue once literacy is acquired.

A robust reading circuit will assure that literacy development will promote oral language, and oral language development will promote literacy—a virtuous cycle of mutual reinforcement and development.

Language at the speed of sight

Mark Seidenberg, also a neuroscientist, completes the triptych. Connecting the sounds of the language to their written representations—typically called “phonics” and “decoding”—is necessary but not sufficient to be a competent reader. Fully and efficiently accessing the spoken language system visually requires accuracy, automaticity, and fluency in processing written language, otherwise known as “reading.”

The title of Seidenberg’s important book, Language at the Speed of Sight, captures the idea neatly. Proficient reading requires a large storehouse of words that are recognized “by sight,” meaning that no decoding needed: You see the word; it’s recognized. Boom.

The more words you recognize by sight, the more efficiently you read not only words but running text as well. A growing storehouse of sight words makes possible fluent reading of increasingly longer and more challenging texts.

To be very clear, developing sight words is completely different from memorizing whole words, which is not an effective way to learn to read or to teach reading. The best way we currently know to help readers create and grow a bank of instantly recognizable words is through a process known as “orthographic mapping,” coined by Linnea Ehri. Words are read by sight

when graphemes [letters representing language's sounds] are connected to phonemes [sounds within the words]. This bonds spellings of individual words to their pronunciations along with their meanings in memory. Readers must know grapheme–phoneme relations and have decoding skill to form connections, and must read words in text to associate spellings with meanings. Ehri, 2020.Following Ehri’s foundational work, here is the best way we currently know to help beginning and early readers start to develop their bank of sight words, promoting “language at the speed of sight” from the very beginning of reading development:

When coming to a word not recognized by sight, first try to decode the word using letter-sound (phonics) skills. Then ask yourself: (a) is it a word I recognize, and (b) does it make sense in its context (the surrounding text and pictures). If the answers are yes, chances are very good the word has been correctly read. If either answer is no, give it another go.

After several successful “mappings” of a word’s spelling to its pronunciation, then to its meaning, the word becomes a sight word and is immediately recognizable. Again, some learners will map a word very quickly, maybe even in one shot; others will require many mappings; most of us are somewhere in between.

As beginning and early readers gain understanding and experience with the sound-symbol system; learn spelling (orthographic) patterns and connect them to word pronunciations and meanings; learn to navigate orthographic irregularities; grow their storehouse of sight words, including irregular words; solidify the connections between written and oral language; engage regularly in reading (and writing), all the while developing oral language and knowledge as they gain increasingly accurate and automatic word recognition and text reading skills; solidifying the “reading circuit,” at some point reading will take off. Reading development will soar if ample reading opportunities continue, and reading is encouraged and supported.

That’s what we should want for all our students. And for everyone.

1. Almost all children learn to speak naturally; reading and writing must be taught. (NB: This first maxim accurately points out there is a fundamental difference between learning oral language compared to learning written language. In a separate post, however, I discussed that the “natural vs. taught” comparison is a bit misleading.)

2. Literacy begins at birth. It is rooted in early social interactions and experiences that include regular exposure to oral language and print. Strong roots tend to produce stronger readers.

3. All good readers are good decoders. Decoding should be taught until children can accurately and independently read new words. Decoding depends on phonemic awareness: a child’s ability to identify individual speech sounds. Decoding is the on-ramp for word recognition.

4. Fluent readers can instantly and accurately recognize most words in a text. They can read with expression and at an appropriate rate for their age. Reading fluency requires comprehension AND it supports comprehension.

5. Comprehension—the goal of reading—draws on multiple skills and strengths, including a solid foundation of vocabulary and background knowledge.

6. One size does not fit all: use student data to differentiate your instruction.

7. Direct, systematic instruction helps students develop the skills they need to become strong readers. Indirect, three-cueing instruction is unpredictable in its impact on word reading and leaves too much to chance.

8. These maxims apply to English Learners/Emergent Bilinguals, who often need extra support to bolster their oral language as they learn to read and write in a new language.

9. We should support students who speak languages or dialects other than General American English at home by honoring their home language and by giving them ex- panded opportunities to engage with General American English text.

10. To become good readers and writers, students need to integrate many skills that are built over time.

“Neonates are more attentive to speech than to any other stimulus.” Bower, T.G.R. (1979). Human development. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, p. 228.

Written characters are letters that represent the speech sounds of the oral language in alphabetic writing systems (sometimes called phonographic) such as English or Spanish. Languages such as Hebrew or Arabic use a partially phonographic script (called “abjad”), so called because primarily consonants are represented in these scripts; diacritics, which are not consistently used, mark vowel sounds. Written languages such as Chinese and Japanese kanji are logographic. They use characters, or graphs, that represent concepts rather than sounds. Regardless of writing system, literacy requires connecting speech sounds to corresponding written symbols then to their meaning. See Stanislaus Dehaene’s masterful Reading in the Brain. (I don’t get a commission if you use this or any other link I provide.)

As I pointed out in a previous post, there are alternatives to help visually and auditorily impaired individuals learn to read printed text. But neither visually impaired individuals using braille nor hearing impaired individuals using a variety of work-arounds will typically acquire the reading fluency and ability that individuals without such impairments do.

Excellent! Love the simplicity.