Trigger warning: This is pretty long. “3-cueing” has, in one guise or another, been at the center of many of our field’s disagreements for a long time. It’s confusing terrain, and my goal has been to try to clarify what we’re talking about because too often we seem to talk past each other or without being clear about what it is we’re talking about. I’m now repeating myself. I hope you can make it through to the end, and of course please weigh in at the comments. Or email me.

Rob and David said in their reply to my critique that “we’ll have to agree to disagree” on 3-cueing. But that will depend on what we mean by 3-cueing and the claim being claimed.

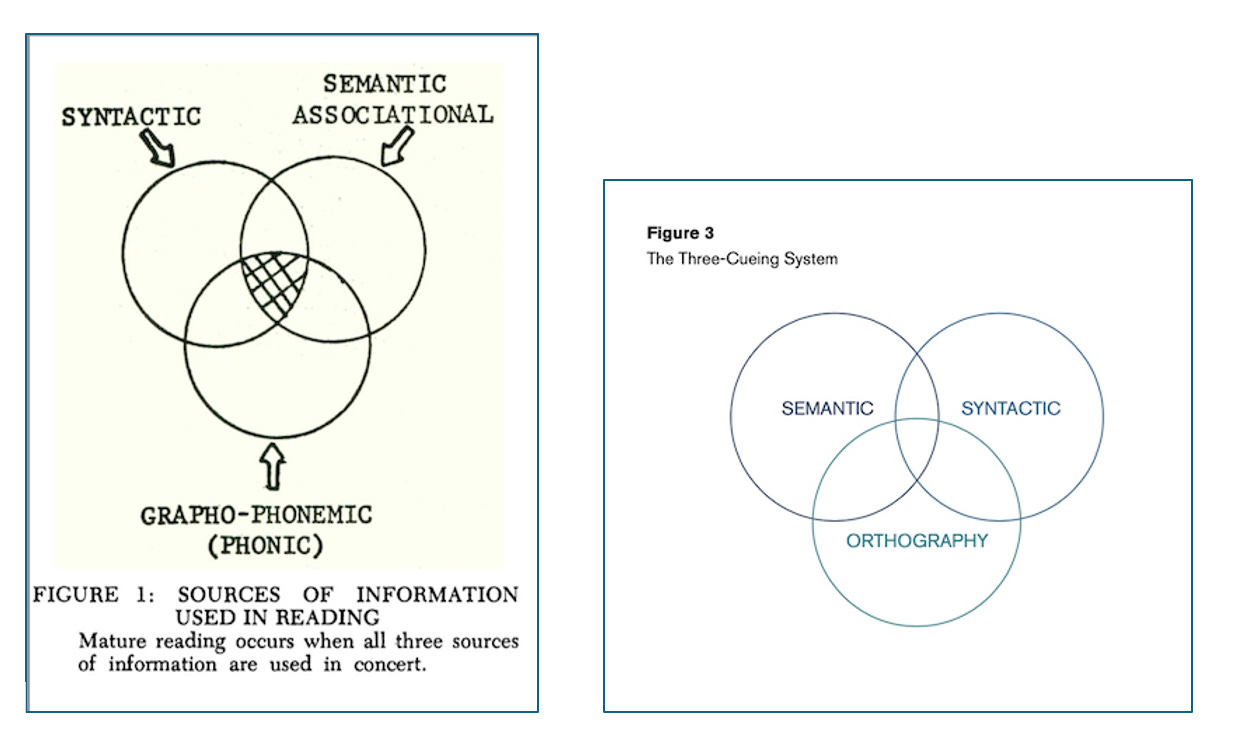

Marilyn Adams did some sleuthing 25 years ago and discovered that David was the originator of the (in?)famous “3-cueing” Venn diagram in a 1976 article. A “cue” is simply a source of information.

The term “3-cueing” did not appear in David’s article, but the diagram below did (Figure 1). The diagram has been amazingly sticky, and “3-cueing” eventually got stuck to it. Or on it.

Next to the figure from David’s article is the version Rob and David included in their book, labeled “The Three-Cueing System” (Figure 3).

Note the caption in small print under Figure 1: “Mature reading occurs when all three sources of information are used in concert.”

The figure and its caption are unobjectionable, as far as they go, in describing aspects of what “mature reading” entails. Certainly there are more current and complicated versions; some are discussed in Rob and David’s book.

But it’s one thing to say the model depicts “mature reading.”

It’s quite another to apply either figure to teaching reading. This is how the 3-cueing claim has come to be understood in the reading world: When teaching learners to read, all three “cues” should be considered simultaneously, because—the assumption goes—they are all equally important when learning to read.

The same claim is made about a descendant of 3-cueing, MSV, which stands for “meaning/syntax/visual.” See below1 for more on MSV.

Whatever it’s called, the claim is incorrect. The most important “cue” when teaching someone to read is what David identified nearly 50 years ago in Figure 1 as “grapho-phonemic.”

All cues are NOT created equal. It is imperative that learners forge strong connections between the sounds of the spoken language and the symbols used to represent those sounds visually, that is, in print.

“Access spoken language visually.”

In a previous post on the differences between oral and written language (see here for a refresher), I quoted neuroscientist Stanislaus Dehaene that reading requires us to “gain the ability to access the spoken language system through vision.” Think about the significance of this statement. The ability to access spoken language…. visually.

What we are innately able to access through one perceptual system—hearing—we need to learn to access through a different one—vision.

That ability is gained by connecting, in the brain (where else?), the sounds of the language (the phonemic side of the hyphen in Figure 1) to how those sounds are represented in writing (the grapho side).

Dehaene and many other neuroscientists have shown that by making this phoneme (sound) to grapheme (written symbol) connection in the brain, a person’s oral language can be accessed by seeing it written. If you can’t access your oral language visually, as print or writing of some sort, literacy is extremely difficult.

Connecting the sounds of the language to the sounds’ visual (i.e., graphic, or written) representations then to the meanings carried by language creates what is referred to as “the reading circuit.” This is what makes reading possible.

(Note there are alternatives to help visually and auditorily impaired individuals learn to read printed text. But neither visually impaired individuals using braille nor hearing impaired individuals using a variety of work-arounds will acquire the reading fluency and ability that typically-seeing and -hearing individuals do.)

But how to teach it?

Neuroscientists themselves will tell you they cannot determine more and less effective teaching methods without classroom and behavioral research. We have such research, and what it has found is that beginning and early reading instruction that prioritizes teaching students to connect the sounds of the language to their written representations—what we typically call “phonics” or “decoding”—provides a significant advantage for learning to read.

There are dozens of studies and many reviews or meta-analyses documenting this. As in any research or scientific enterprise, studies can point in different directions. But there is no question that the bulk of the research shows that in beginning and early reading, phonics instruction—explicit teaching of sound-to-letter connections—provides an advantage to beginning and early readers and to students having difficulty learning to read.

If you doubt this, and have an open mind rather than unshakeable contrary belief, please find extensive documentation at the Evidence Advocacy Center, or EAC. Or go to a recent commentary I wrote that has links, particularly this one.

Agree to disagree?

So….. if by 3-cueing Rob and David mean what David meant in his 1976 article, that “mature reading” involves using syntactic, semantic, and grapho-phonemic “sources of information,” I willingly agree.

But if they mean that 3-cueing tells teachers that when teaching beginning and novice readers they should teach all three “cues” simultaneously and as equally important, we disagree.

But…. I can’t just leave it at that.

Here are the facts, as I understand them:

• Explicit teaching of sound-to-letter connections increases the likelihood that novice readers and students having difficulties will learn to read.

• Some students learn to read even in classrooms that do not adequately emphasize teaching of sound-to-letter connections, such as classrooms using 3-cueing.

• However, too many students in classrooms that do not adequately emphasize teaching sound-to-letter connections will be deprived of instruction they need to help them make the connections necessary for them to access their oral language visually. (And fluently, too, which is a whole ‘nother topic. See Mark Seidenberg’s Language at the Speed of Sight. Just fyi. I don’t get any commission if you buy with this link.)

Tim Shanahan recently wrote in his blog, that “in the 60 years since three-cueing was proposed, there is no direct evidence that teaching it improves reading.” If Rob and David reply to me or to Tim, they will undoubtedly cite Donna Scanlon’s work on ISA (the “Interactive Strategies Approach”) to contradict this statement. I’ll just note that Tim said in the same blog that Scanlon’s

review of those studies [in a 2020 article in Reading Research Quarterly] is misleading. She draws conclusions that the original researchers wisely did not draw… Context definitely plays a role in decoding and decoding development, but it is not the role 3 cueing advocates cling to.Tim uses “context,” a more general term subsuming syntactic and semantic, the terms Rob and David (and David nearly 50 years ago) used to invoke “cues” other than letters and sounds. The point is that these other cues/sources of information, whether referred to as context, syntax, or semantics, are not irrelevant.

But they are not, as Tim says, “the role 3 cueing advocates cling to.” Instead, they are secondary to grapho-phonemic (or orthographic) cues.

This was made clear to me in an article by Linnea Ehri and her colleagues reporting the results of an intervention for emergent bilingual students having difficulty in first-grade reading. I’ll have more to say about emergent bilinguals (sometimes known as English learners), reading, reading wars, etc. in a future post.

For now, what’s relevant is how Ehri describes the role of, first, phonics/decoding, then context (including pictures!), to read and recognize words:

Students were encouraged to decode unknown words by relying on their letter–sound knowledge and then cross-checking with meaning and pictures to confirm the identities of the words.The same procedure for word reading and recognition—decode unknown words using letter–sound knowledge; cross-check with context to confirm—applies to English speakers as well as to English learners. The specific issue her study addressed was that students who are learning English as they learn to read it need English oral language support and instruction so that they know the meanings of the words and the text. Otherwise they cannot “cross-check with meaning,” nor can they “confirm the identities of words” if they don’t know the words.

We can certainly claim three (or some number) of cues are being used. But what Ehri describes is decidedly NOT 3-cueing as it has come to be understood and practiced—that teachers should teach all three “cues” simultaneously and as equally important for reading words and text.

Some students will learn to read despite this unhelpful advice. Many others will be seriously disadvantaged.

Two more points (basically disclaimers)

Sorry, I keep trying to be brief.

• Phonics is not first, only, & put all else on hold. No one should conclude that I’m saying phonics is the first or only thing that matters in learning to read, or that everything else can be put on hold until students can decode. It is beyond dispute from reading research that oral language development, which includes vocabulary, knowledge, all aspects of language proficiency, and probably other things such as metacognition and motivation, are also essential for, or at least contributors to, reading development.

Remember: Learning to read involves constructing the reading circuit that enables accessing spoken language through vision. Connecting sounds and symbols (i.e., letters) is merely, but crucially, a means toward that end. If our oral language is limited, so too will be our reading abilities. Oral language development, including knowledge and associated vocabulary, is also crucial, before and while learners forge a tight linkage between the sounds of the language and how those sounds are represented in print.

Learning the sound-symbol system is finite. But language development and knowledge are not. They can and should continue indefinitely as we experience and learn throughout our lives. Every advance in language proficiency and knowledge also advances reading development; reading development then repays the favor by advancing language proficiency and knowledge growth. But only if the sound-symbol connections are automatic, robust, and fluent.

• There’s such a thing as over-teaching phonics. It should follow from the preceding that as important as phonics is, it’s just as important that language and knowledge development receive adequate attention. And since time in school is limited, we need to be extremely careful and strategic in how students and teachers spend time.

The best demonstration of this that I know has been by Carol Connor, the (sadly) late, great UC Irvine professor who demonstrated the importance of ongoing assessment to monitor progress and the danger of too much phonics when students actually need more work on meaning and comprehension, illustrated in this five-minute clip. The danger of too much what she calls “code-focused” (vs meaning) instruction starts at the three-minute mark; but the entire clip is worth watching.

For more information about Connor’s work and the company founded based on her research, see here.

To dig even deeper into this challenging question, see this blog Bursting with Knowledge: Are We Overteaching Phonics?” by reading specialist (and reading sage) Harriett Janetos.

There’s more to say that follows from the above, e.g., explicit phonics instruction increases the likelihood of reading success but provides no guarantee, and while phonics instruction’s effects on reading acquisition are real (technically, “significant”), they are more modest than many “science of reading” advocates claim.

I hope to revisit these in a future post. This one is long enough. But if interested, see here in the meantime.

Next up in Tierney & Pearson reply IV (and final): What counts as reading, getting personal, and claims worthy of fact-checking.

The term MSV, sometimes depicted as M/S/V meaning, syntax, and visual, names the “sources of information” used for reading. This version of “3-cueing” (although, again, it was not referred to as 3-cueing) apparently originated with Marie Clay, of Reading Recovery fame, but MSV was popularized as a strategy for teaching reading by Lucy Calkins, known to millions for her “Units of Study” reading curriculum.

Calkins explicitly distanced herself from the term 3-cueing: “I do not know anyone … who defines his or her method for teaching reading as ‘the three cueing system.’” (Quotes are from Units of Study training materials I cited in a blog about the program.) Yet she told teachers that a “first encounter with the text is a perfect time to practice using multiple sources of information (MSV) to tackle tricky words.”

So, no to 3-cueing, but yes to “multiple sources of information”: M (meaning), S (syntax), and V (visual). Coincidentally, there are three. Now that’s tricky! (See the blog for more details about Units of Study and Calkins’ evasiveness around her terminology, including that other lightning rod term, “guessing.”)

This is incredibly useful. It’s rich, so being long is an advantage, not a problem.

I read the whole thing on my phone (and I strenuously dislike reading on my phone). I’m sharing this link far and wide and hope others will amplify it.

Claude, this centerpiece and the trove of links (especially - for me - the hard- to-locate Marilyn Adams sleuthing work on the origins of 3 cueing) could constitute the bedrock syllabus of a superb reading course for teacher prep.

Can’t thank you enough for taking the time to do thoughtfully lay this out for us. 🙏🏼

This is one of the most intellectually honest pieces I've read about the thorny subject of 3-cueing. With reference to Ehri's study, you state:

"The specific issue her study addressed was that students who are learning English as they learn to read it need English oral language support and instruction so that they know the meanings of the words and the text. Otherwise they cannot 'cross-check with meaning,' nor can they 'confirm the identities of words' if they don’t know the words."

This exactly describes my experiences working with my first grade intervention students--and it doesn't just apply to my EL's. When they read our decodable stories with the words 'fig', 'shed', and 'crib', they invariably decode these words beautifully but don't know what they mean. I can then direct them to the illustrations so they can add these words to their receptive vocabulary, and I share with them that I grew up knowing about figs because my Greek mother insisted on planting two in our backyard.

Thank you for such a comprehensive piece!